Climbing and musculoskeletal considerations

by Martin Krause

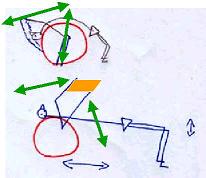

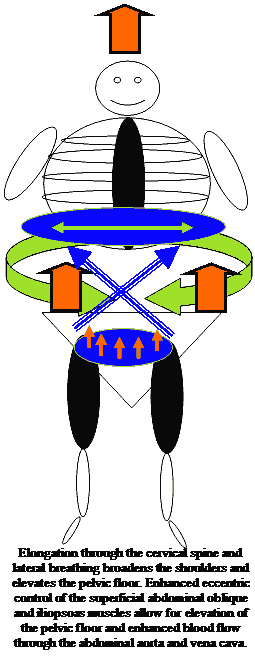

Good climbers use a combination of strength, endurance and flexibility. Power is developed by the arms through an upward throwing action of the arms, which instigates efficient eccentric muscle lengthening decelerating forces (rather than concentric - muscle shortening). Additionally, they are able to facilitate kinetic energy across the chain of movement from toes through the legs and pelvis into the trunk and torso.

Ideal posture

Ideal climbing involves

- extended arms to hang from

- thoracic extension, lateral flexion and rotation

- hip external rotation

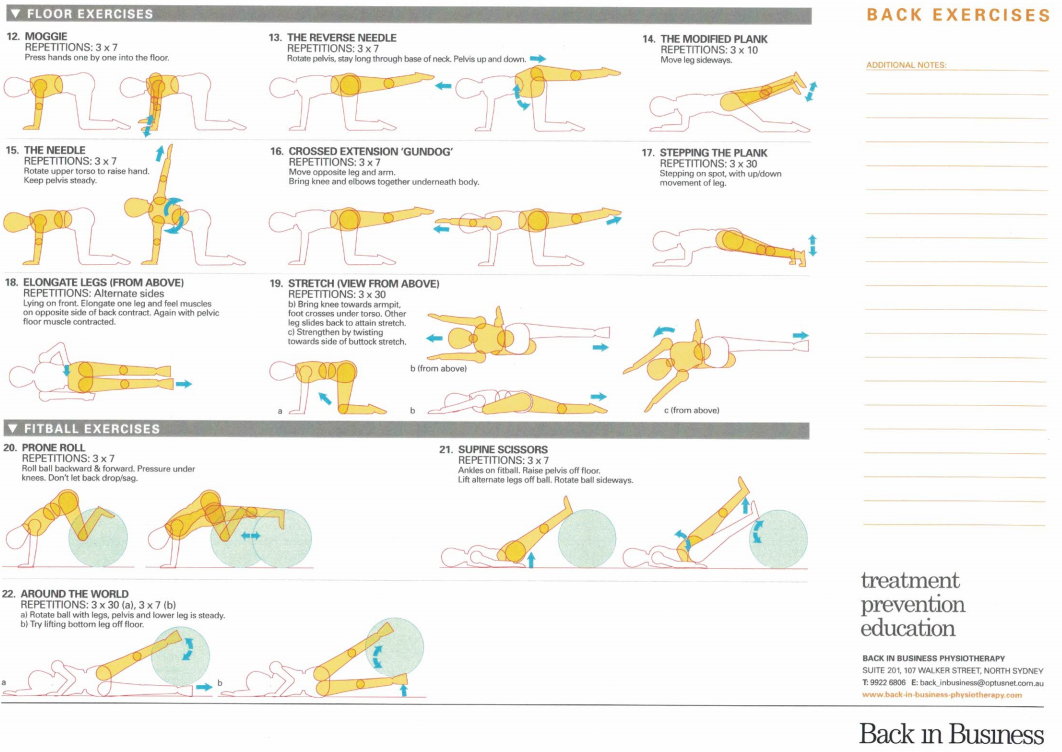

- knee flexion and slight heel rise to develop power through the legs

"An inch is a mile"

In climbing, 'an inch is a mile' refers to delicate foot and hand placement where body length through the elongation of the thorax with thoracic ring elevation. The shoulder blade needs to elevate and allow the thorax to hang from it.

Restrictions of thoracic rotation results in excessive contralateral gluteal contractions. Inadequate shoulder flexion due to limited thoracic ring extension can cause reduced contralateral gluteal activity

Gorillas on the Cliff

Climbers can develop a 'gorilla-like' posture due to over emphasis on

- grip

- arm flexion

- a '6 pack'

Since the abdominal muscles cross the lower 6 ribs, sufficient trunk core stability should not compromise the mobility (especially rotation) of the thorax.

Excessive development of the low thoracic - upper lumbar erector spinae can create

- reduced gluteal muscle strength,

- reduced diaphragmatic breathing,

- increased psoas major tightness and

- reduced core stability.

![]()

Postural problems associated with climbing could lead to musculoskeletal injury

- Climbers may develop a gorilla-like appearance due to the unique nature of the sport

- Gorilla-like appearance alters the centre of gravity of various limb and trunk segments

- this may lead to shoulder injuries, headaches, neck, arm and back pain

Stomach crunches or 'curls' may cause

- tightness of the rectus abdominis ("6 pack") and external obliques

at the expense of

- weakness of the transverse abdominis muscle

- increased thoracic kyphosis (rounded back)

- reduced diaphragmatic lateral expansion

which contributes to the gorilla posture resulting in

- altered thoracic biomechanics which affects active SLR and active PKB suggesting reduced lumbopelvic rhythm (gluteal : hamstring timing)

- reduced strength in the lumbo-pelvic-hip musculature

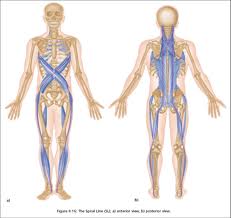

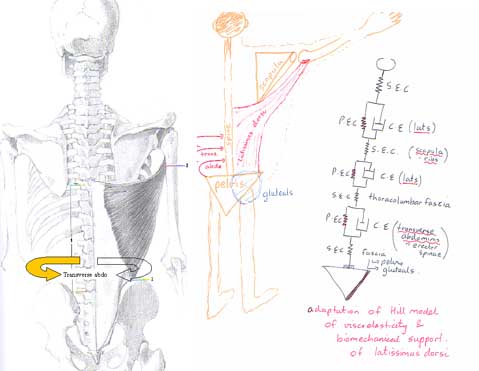

- reduced gliding of the myofascial trains extending from the superficial front line of the latissimus dorsi to the superficial back line of the thoracolumbar fascia and the gluteals

Myofascial Trains

Arm elevation normally results in contralateral gluteal and transverse abdominal activity in the 'wall plank' position

Power = strength, speed and flexibility

Training should involve functional movement patterns, whereby some muscles are used as stabilisers whilst others are used as mobilisers. The deeper lying endurance muscles tend to be the stabilisers and are frequently found to cross only one joint or work in an area of limited movement. The mobilising, power muscles, tend to be the 'energy straps' crossing more than one joint and conferring kinetic energy to the movement system. A balance between mobility and stability needs to be attained.

Overhead reaching

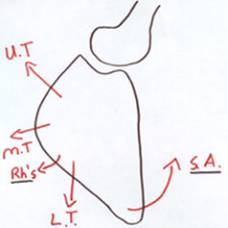

This requires extension and rotation flexibility in the thorax, as well as front of shoulder and chest flexibility. Balanced with this flexibility should be strength in the serratus anterior so that the thoracic rings can 'hang off the arms'.

The serratus anterior inter-digitate with the abdominal muscles which cross the lower 6 ribs. So, as the upper rib cage and thoracic rings elevate upwards, an eccentric lower thoracic ring stabilisation must take place to bring the semi squat power of the legs into play.

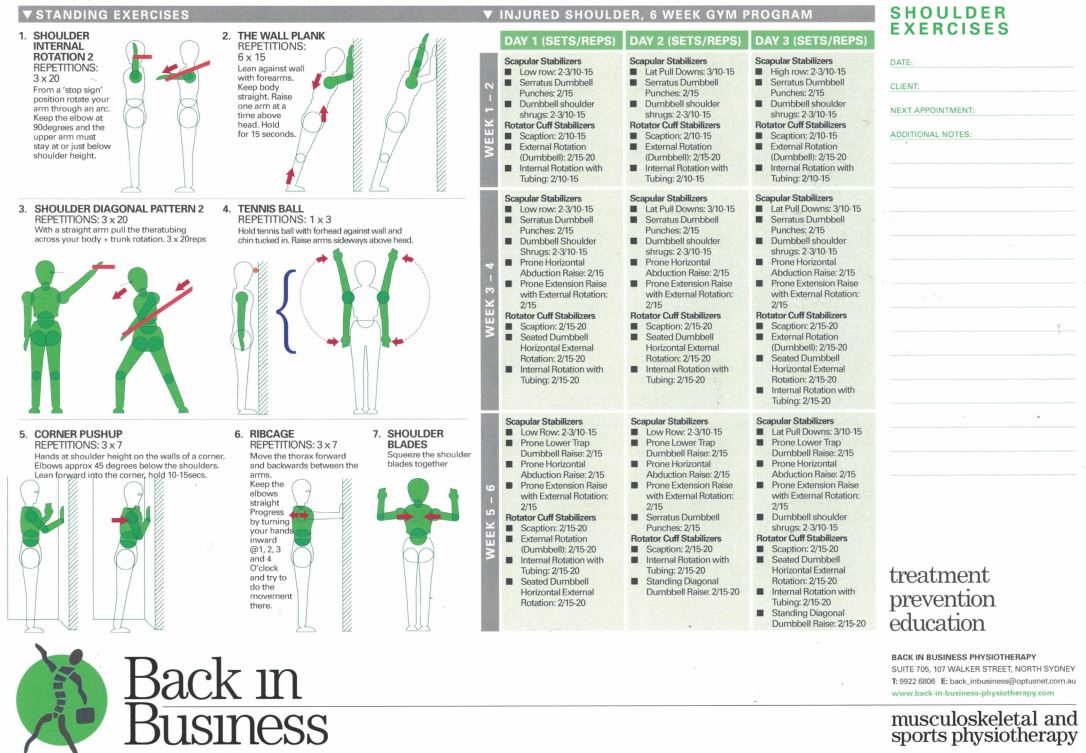

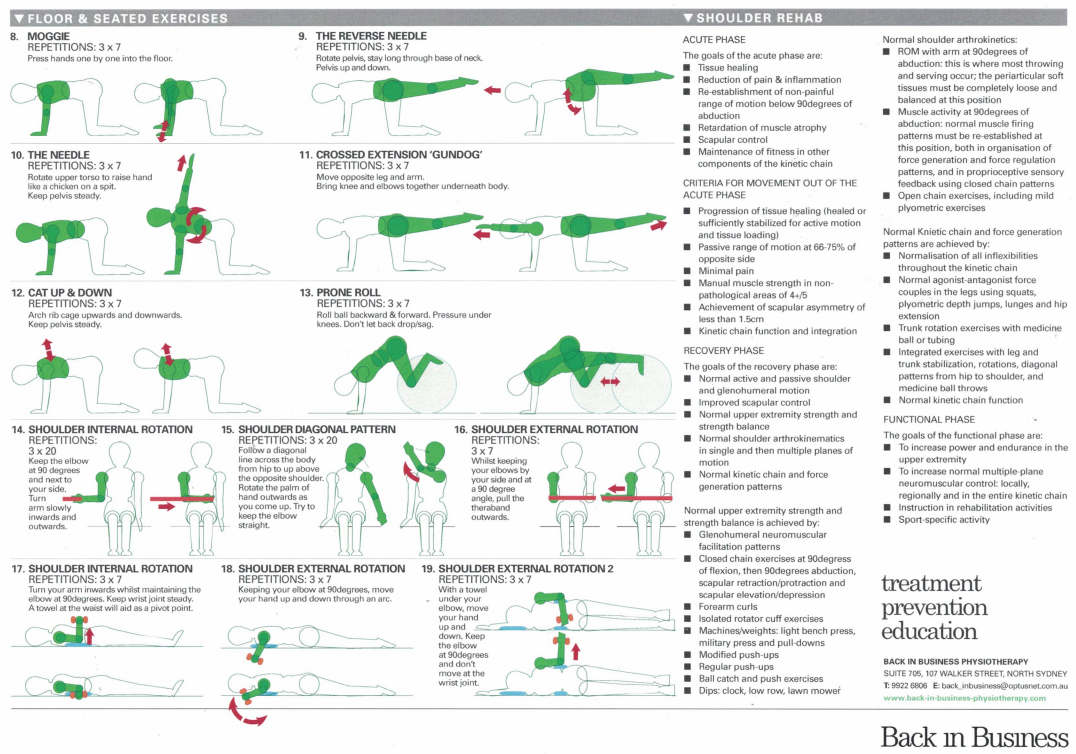

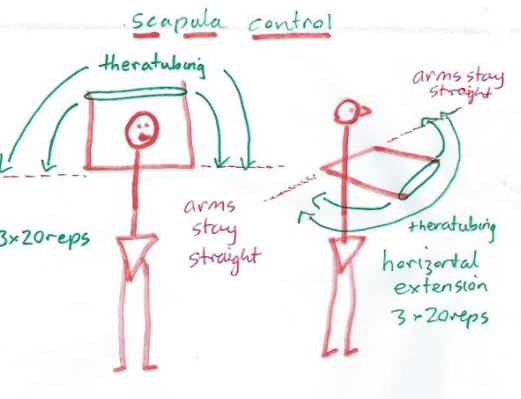

Development of the scapular stabilisers

An interplay with the muscular slings, their stabilisers and mobilisers comes into play.

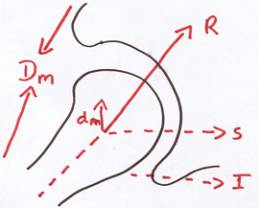

The shoulder joint has a shallow socket which provides a surface for the large 'ball' (same size as the hip!) to interface. To maintain stability, the rotator cuff muscles need to provide consistent support and pressure around a centre of rotation. Since these muscles are attached to the scapula (shoulder blade), the shoulder blade requires correct and consistent orientation, otherwise the rotator cuff function is rendered useless (see example below if only the rhomboids [Rh] {and in fact levator scapula} were used).

Read more about stability elsewhere on this site

Excessive and prolonged reaching

- results in tight serratus anterior and pectoral (chest) muscles

- contributing to excessive strain on the blood vessels, nerves and joints of the shoulder - neck - arm complex (TOS = thoracic outlet syndrome)

- creates excessive low thoracic erector spinae activity contributing to loss of costal expansion, as well as reduced diaphragmatic rhythm

- has been associated with impingement in the supraspinatus (superior rotator cuff and subacromial bursa) muscle leading to discomfort in the shoulder with loss of muscle power during activities above shoulder height

- Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular (collar bone joints) joints may become inflamed

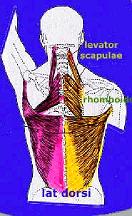

Overhead reaching can

- result in excessive strain on the back and shoulder blade muscles

- cause the rhomboids and levator scapulae to become long and weak

- facilitates the latissimus dorsi to become short and strong

- scalene muscle tightness, rib elevation and circulations compromise, similar to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

Training

- the trapezius muscles requires synergistic (complimentary) action by the

- latissimus dorsi

- erector spinae (back)

- oblique and transverse abdominal muscles (not the "6-pack"!!)

- the deltoid muscle requires synergistic action by the

- internal oblique and transverse abdominal muscles

- contralateral gluteal activation

- lumbar erector spinae activity

- the serratus anterior needs synergy with the

- external obliques

- intercostals

- diaphragm

- should replicate the combination of muscle synergies in the most climbing functional way as possible.

- arm strength requires gluteal strength

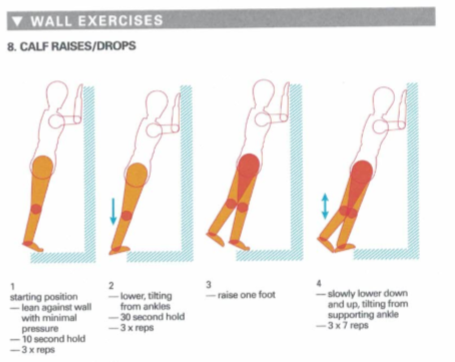

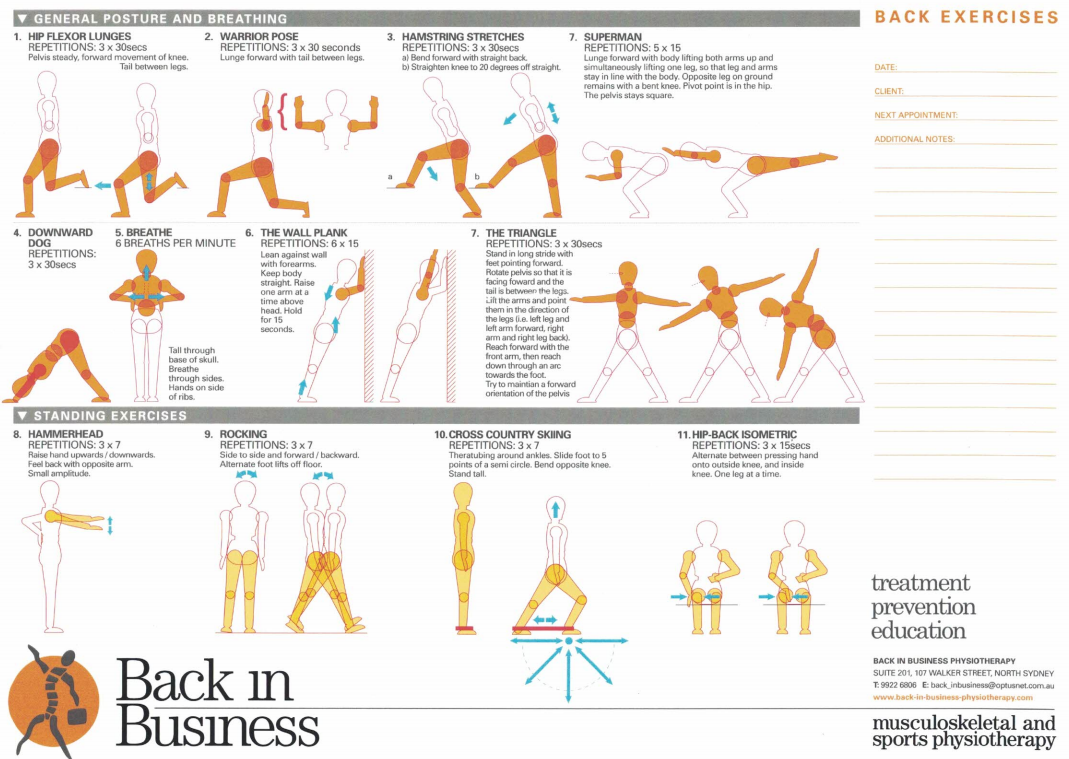

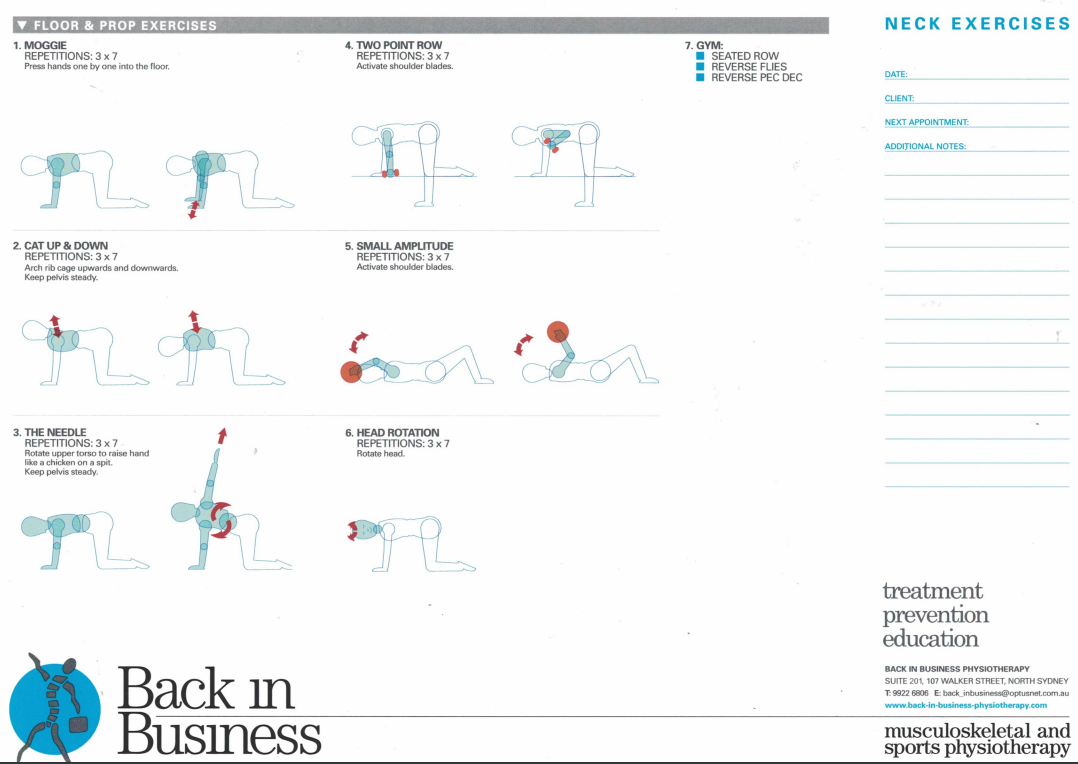

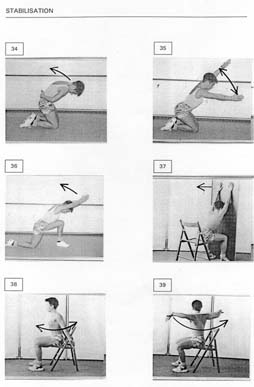

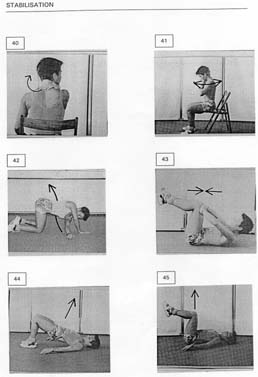

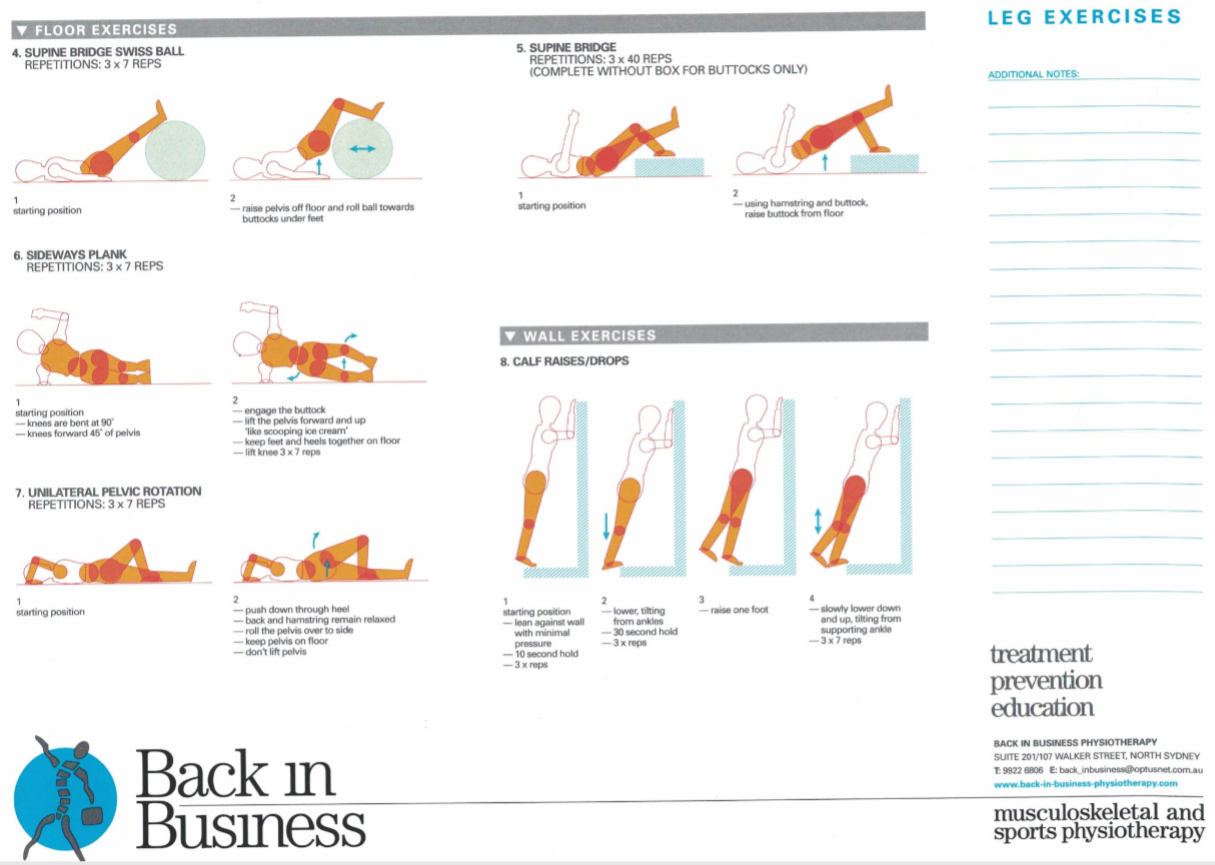

Bridging exercises

with the Swiss Gym ball and elastic tubing allows

- functional activity which stretches the pectoral girdle and "6 pack"

- strengthening of the abdominal, spinal and shoulder blade muscles

- dynamic stability of the pelvis and hips allowing enhanced freedom of movement on the cliff face

"Prone bridging" allows abdominal, pelvic, trunk and arm control to be trained

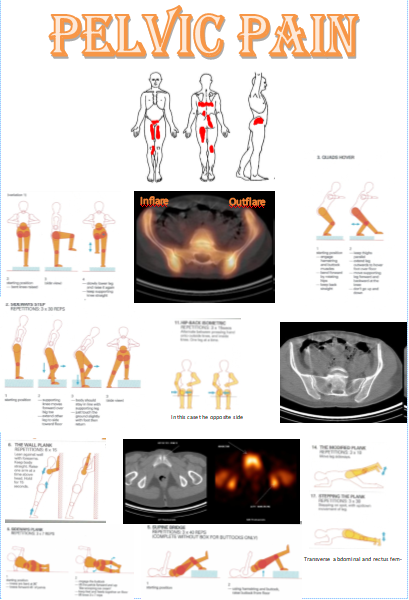

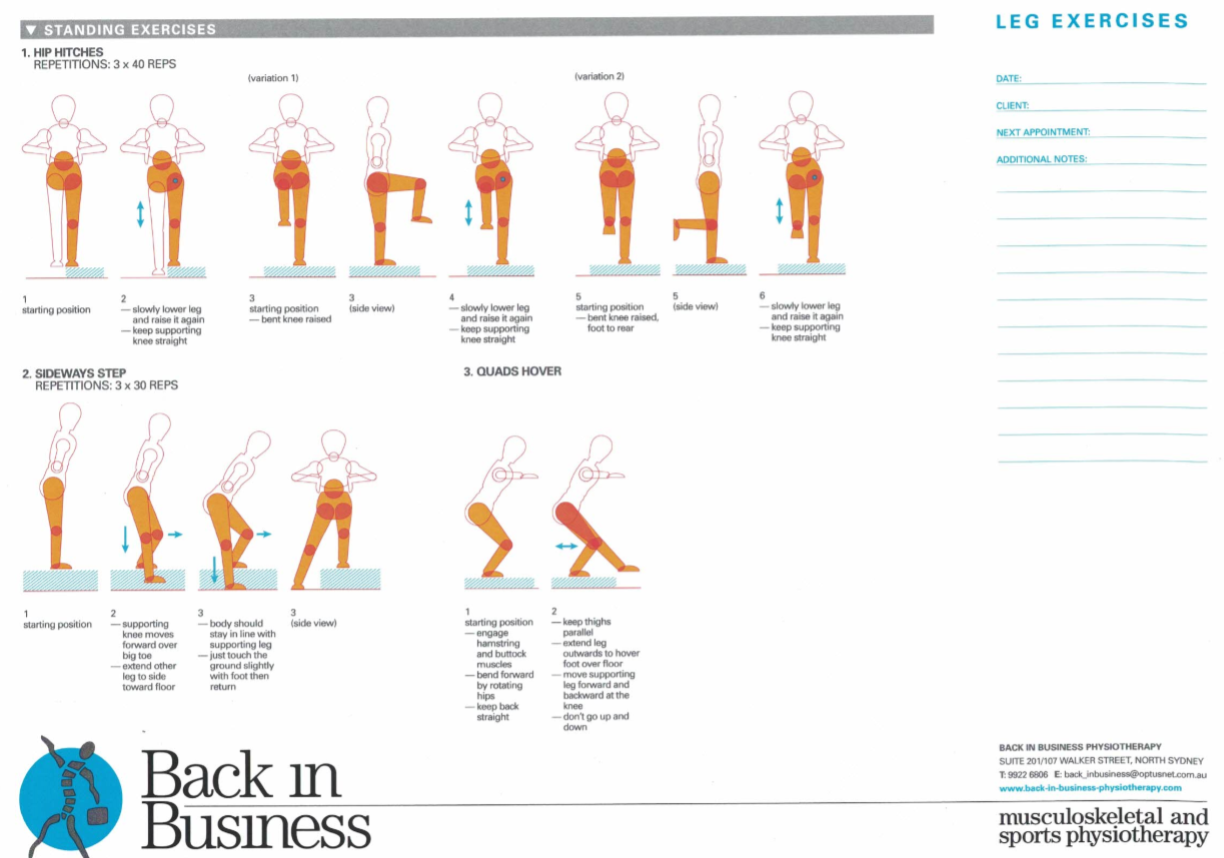

Supine bridging can be used to develop gluteal and lower abdominal strength, especially when done, one legged. with the thighs consistently parallel. Whilst modified planks and side planks can be used to develop arm, gluteal and abdominal strength simultaneously. The following example from a client with pelvic pain demonstrates the muscle synergies required, across the body, and in particular around the pelvis, for functional integrity.

These exercises and modified versions of these can be used to improve climbing ability and agility.

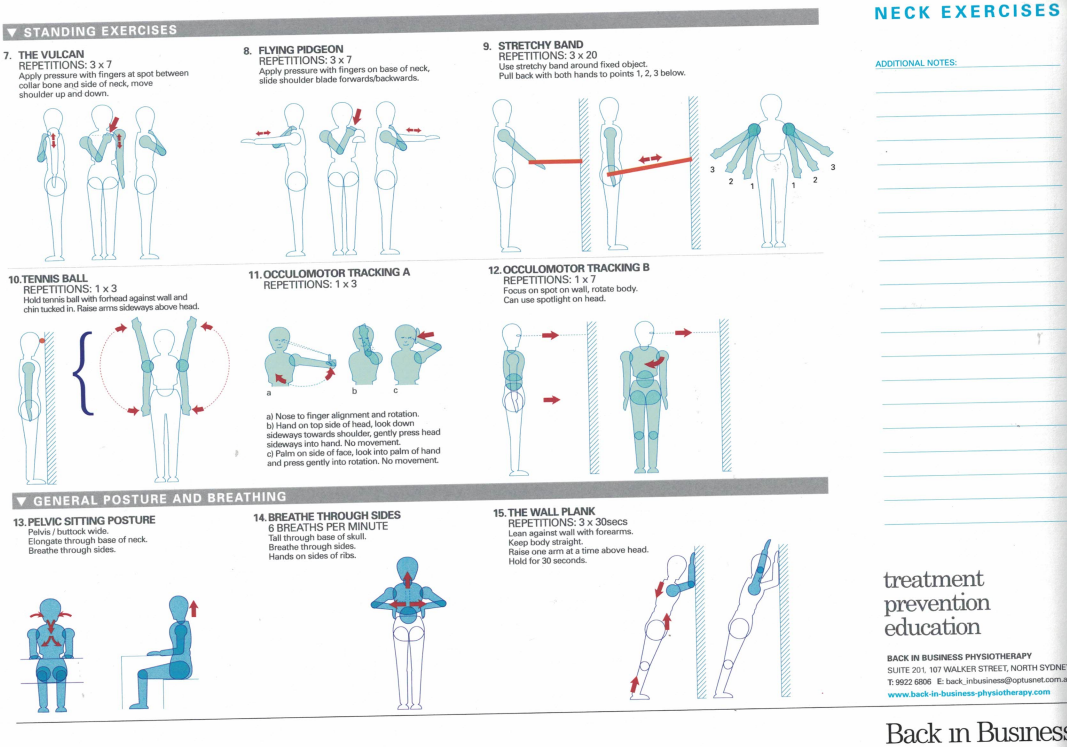

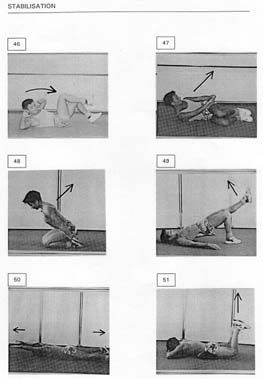

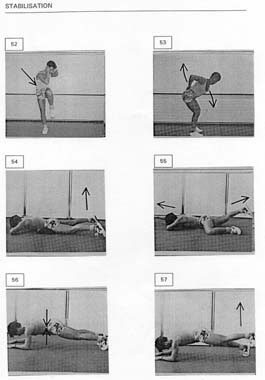

Functional exercises

In climbing, ideally there are three points of contact, meaning that three points are either statically or dynamically stabilising whilst a limb is moving off the rock. The following describes a series of exercises for stability whilst moving various body parts

Modifications can be made into climbing patterns, such as semi squat rather than sitting

To reduce a "poked chin" the deep neck muscles need activation and the thoracic rings require elevation through Alexander technique and lateral diaphragmatic breathing

Clinical observations

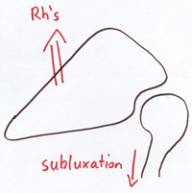

Clinically, people fall into two broad categories - the hypermobile or the hypomobile. Hypermobile people generally work with their ballistic power generating muscles, using inertia to stabilise. These ballistic muscles can be long and strong but also long and weak if they haven't been appropriately conditioned. Hypomobile people tend to use their slow twitch endurance muscles and have short tight ballistic muscles. General rule of thumb is that 'floppies' need to work on endurance and stability, whereas 'stiffies' need to work on their flexibility and ballistic power. It is also possible to have hypermobile soft tissue (lax joints) but tight protective overlying muscles. Floppies tend to be good at 'pulling' into themselves, whereas 'stiffies' tend to be better able to push away. Ideally, individuals should work at what they aren't naturally endowed with to gain a 'musculoskeletal' protective balance. Frequently, one finds the 'floppies' in the yoga class and the stiffies in the pilates class when it really should be the other way around. Interested readers should read the Joint Hypermobility Syndrome and Ehlers Danlos Syndrome section elsewhere on this website. Too much pulling, with too little stability can lead to shoulder subluxation and even posterior dislocation. These shoulders need to have the soft tissue at the back of the shoulder 'buffed up' and be very conscious of 'scapula setting' when commencing movements.

Ideally, muscle synergies are developed where the nett gain of all muscles working at their most efficient level to gain a mutually beneficial movement outcome is what is desired. In such a scenario, the distinction between agonists and antagonists, postural muscles and ballistic muscles becomes superfluous, let alone one body part being dominant over another. Interested readers should read 'game theory' and 'deterministic chaos' elsewhere on this site

Voluntary Posterior Shoulder Subluxation : Clinical Presentation

A 27 year old male presented with a history of posterior shoulder weakness, characterised by severe fatigue and heaviness when 'working out' at the gym. His usual routine was one which involved sets of 15 repetitions, hence endurance oriented rather than power oriented. He described major problems when trying to execute bench presses and Japanese style push ups.

In a comprehensive review of 300 articles on shoulder instability, Heller et al. (Heller, K. D., J. Forst, R. Forst, and B. Cohen. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder: recommendations for a classification. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 113:228-231, 1994) concluded that posterior dislocation constitutes only 2.1% of all shoulder dislocations. The differential diagnosis in patients with posterior instability of the shoulder includes traumatic posterior instability, atraumatic posterior instability, voluntary posterior instability, and posterior instability associated with multidirectional instability. Laxity testing was performed with a posterior draw sign. The laxity was graded with a modified Hawkins scale : grade I, humeral head displacement that locks out beyond the glenoid rim; grade II, humeral displacement that is over the glenoid rim but is easily reducible; and grade III, humeral head displacement that locks out beyond the glenoid rim. This client had grade III laxity in both shoulders. A sulcus sign test was performed on both shoulders and graded to commonly accepted grading scales: grade I, a depression <1cm: grade 2, between 1.5 and 2cm; and grade 3, a depression > 2cm. The client had a grade 3 sulcus sign bilaterally regardless if the arm was in neutral or external rotation. The client met the criteria of Carter and Wilkinson for generalized ligamentous laxity by exhibiting hyperextension of both elbows > 10o, genu recurvatum of both knees > 19o, and the ability to touch his thumb to his forearm

Fingers, elbows and wrists are also common places for climbing injuries. Taping can be particularly useful in protecting and unloading tendinous structures.

Conclusion

Seek guidance from your physiotherapist as the ultimate aim is to improve your power-weight ratio without inducing an injury. An optimal combination of strength, stability, and mobility needs to be acquired across the the entire body. The following videos should give you an insight of some of the things which are possible. Laterality of thought, improvisation and proper progression of exercise should allow refinement of climbing technique as well as reduce the risk of injury.

Hip stabilisation and thoracic mobilisation

Several exercises exist which stabilise the hip and shoulders whilst mobilising the thorax.

Swiss Ball exercises can also be used to improve thoracic ring stability

Thoracic strengthening regimes should be instigated to maintain the ring alignment

Stretching regimes - 'don't let the tail wag the dog'

Many people stretch their limb muscles. However, if the thorax is the 'driver' of limb muscle tension, then the thorax needs to be nullified beforehand and/or involved in the process of stretching. For example both hamstrings and quadriceps can be stretched with lateral flexion and lateral breathing of the diaphragm. Classic moves out of yoga such as the 'down dog -> high plank -> warrior pose -> triangle' can involve rib cage movements.

Don't forget the calf muscles!

Summary of leg, back and shoulder exercises

Front, back, inside, outside and spiral 'slings'

References

Shoulder stability : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/shoulder.html

Hypermobility : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/we-treat/ehlers-danlos-syndrome.html

Joint Stability : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/stability.html

Game Theory and Cortical Resources : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/health-advocacy/exercise-and-the-immune-system-during-covid-19.html

Pelvic - Hip - Lumbar stability : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/we-do/muscle-energy-techniques.html

Thorax : https://www.back-in-business-physiotherapy.com/we-treat/thorax.html

Conceptualised whilst working and living in the mountains of Switzerland and the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, NSW, Australia (!988-2001)

Uploaded : 13 October 2020

Updated : 11 December 2020